Not everyone knows that here, in the United States, we don't pick chestnuts: yes, that autumn ritual that brings people with a wicker basket and gloves to crouch down to look for these spiny balls that guard the precious chestnuts simply does not exist. The reason is not causal and is linked to a very sad story, a dramatic example of how the introduction of invasive species can have devastating consequences on natural ecosystems. The story, in fact, has to do with a botanical tragedy that struck North America in the twentieth century, which ended with the disappearance of the American chestnut tree.

What is The American Chestnut And Why Has it Disappeared?

To tell this story, a premise must be made: there is not just one chestnut. The plant scientifically called Castanea has given rise to different species: the chestnuts that is commonly eaten in Europe come in particular from Castanea Sativa. The other varieties are Castanea crenata, also called Japanese chestnut, Castanea dentata, which is precisely the American chestnut and other lesser-known species such as Castanea mollissima, the Chinese chestnut, Castanea henryi, Castanea neglecta, Castanea ozarkensis, Castanea pumila, Castanea seguinii.

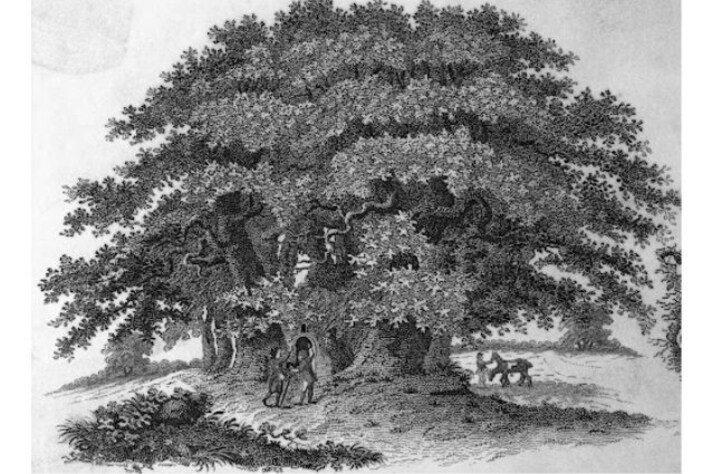

The American chestnut is, or rather was, a specific variety of the eastern territories of the United States: a majestic tree, very long, whose fruits were used as food for both communities and wildlife. At the beginning of the twentieth century, an Asian parasitic fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica, was accidentally introduced into America on imported chestnut plants. This fungus, highly pathogenic for the American chestnut, caused a disease called "chestnut canker " that spread rapidly through the forests. An unstoppable spread: the spores of the fungus spread easily through the air and insects, infecting the trees and causing lethal lesions to the bark. In a few decades, billions of American chestnut trees died, transforming vast areas of forest into stands of dead trunks.

The disappearance of the American chestnut had a devastating impact on the ecosystem, altering the composition of the forests and reducing biodiversity: many animal species, including insects, birds and mammals, depended on the chestnut for food and a habitat. In addition, the lack of roots of the dead trees made the soil more vulnerable to erosion. The disappearance of the chestnut also had a negative impact on the local economy, particularly in rural areas where chestnut harvesting was an important activity.

Attempts to Recover the American Chestnut

In recent decades, several researchers have worked hard to find solutions to the problem of chestnut cancer and recover this variety. Several approaches have been developed, including hybridization, that is, crossing the American chestnut (the few surviving plants) with Asian species resistant to the fungus, a bit like what happened with the vine in Europe, biocontrol, that is, studying methods to control the spread of the fungus using other organisms, and finally genetic engineering, that is, developing genetically modified chestnut plants resistant to the fungus. Although the road is still long, there is hope of bringing the American chestnut back to our forests: thanks to the efforts of researchers and the passion of many enthusiasts, the dream of seeing the majestic American chestnut trees again could soon become reality.

Do Americans Eat Chestnuts, Now?

Americans do eat chestnuts, but let’s be honest—they’re not exactly a year-round staple. For most of us, chestnuts pop up during the holidays, roasted and cozy, like something straight out of a Bing Crosby song. While you might find them on festive menus or being sold hot on city streets come winter, the reality is, most chestnuts in the U.S. are imported. The homegrown chestnut industry is small, so we rely heavily on imports, particularly from Italy, China, and sometimes even Turkey. These countries keep us supplied with that nutty goodness, so we can enjoy our classic holiday chestnut dishes, even if the nuts themselves have crossed an ocean to get here. That might, however, soon change, if the legendary American Chestnut tree will make a comeback!

;Resize,width=767;)